Why your event-driven architecture may actually be a distributed monolith

We implement Kafka, rename services to microservices, and... often end up with a system where one small change requires updating half the code and coordinated deployment. Sound familiar?

The problem isn't with the technology – neither Kafka nor RabbitMQ are to blame. The mistake lies in event modeling and how we understand communication. Today, we'll break down the anti-patterns I see most often. Get ready for a moment of reflection.

What is an event? It is a fact, not a state change

At the heart of EDA problems lies a fundamental misunderstanding of the difference between a business fact (Event) and a state change (State Change).

If you publish an event that sounds like an SQL query, you're on the wrong track. An event is something that has happened, has business significance, and is irreversible. It is not “Row number 22 has been updated.”

What to avoid: CRUD sourcing and property sourcing

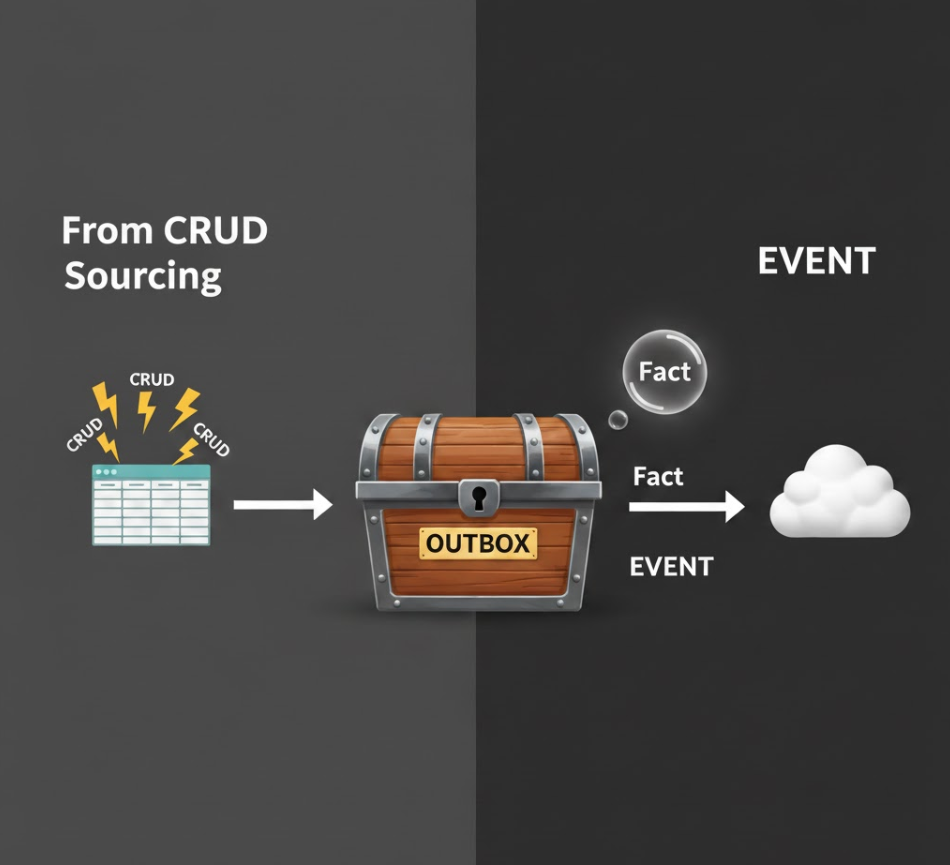

The worst anti-pattern is CRUD Sourcing, which is publishing events based on database operations: Inserted, Updated, Deleted. Using Change Data Capture (CDC) to automatically push these changes to the queue is a fast track to disaster. When a consumer sees a reservation_updated event, they must immediately query the reservation service to check what has actually changed. This results in tight technical coupling.

The second, slightly more subtle, is Property Sourcing. The events are business-related, but too granular, e.g., guest_first_name_changed, guest_email_updated. This approach leads to an avalanche of events that are irrelevant to consumers. Instead, group them into one rich fact that matters:

# Instead of

# guest_first_name_changed(old_value: "Jan", new_value: "Piotr")

# guest_address_updated(city: "Warszawa", postal_code: "00-001")

# Do that:

{

type: "GuestPersonalDataRefined", # The business fact

payload: {

guest_id: "G123",

changes: {

first_name: { from: "Jan", to: "Piotr" },

address: { city: "Warszawa", postal_code: "00-001" }

}

}

}Harnessing clickbait: clickbait events

Remember when you click on a catchy headline and get a hopelessly short article that only forces you to look for information elsewhere? In architecture, we call this a Clickbait Event.

It is an event that contains only minimal information, usually just an ID (reservation_id: 500) and type: reservation_status_updated. This forces every subscribing module to immediately perform a synchronous query (REST/RPC) to the producer service to obtain the full reservation status.

Consequences of event clickbait

We have two main consequences.

- Race Conditions: The event may arrive faster than the producer's database can update. The consumer asks for the reservation status and receives old information.

- DDOS-ing problem: Many consumers simultaneously query the producer about the status in a short period of time. We begin to create systems for mutual self-destruction.

Solution: rich events and outbox

The event must be rich. It should contain all the data necessary for the consumer to make a decision. If payments require the amount and type of reservation, include them there!

To ensure consistency, use the Outbox Pattern. The business state record and the event record in the Outbox table must be part of the same database transaction. A dedicated process safely publishes events from the Outbox table to the queue.

-- OUTBOX PATTERN: save in one transaction

BEGIN;

-- 1. save changes

UPDATE reservations SET status = 'CONFIRMED', updated_at = NOW() WHERE id = 123;

-- 2. Safe business fact in Outbox table

INSERT INTO outbox_events (event_type, aggregate_id, payload)

VALUES (

'ReservationConfirmed',

'123',

'{ "guest_id": "G456", "total_price": 500.00, "room_type": "DELUXE" }' -- Bogaty payload!

);

COMMIT;Communication is not just shouting: Where are the commands?

If all communication in your system is based on events (passive information about what has happened), it resembles a room full of shouting people. No one gives anyone any orders, everyone just reports on their achievements.

This leads to Passive-Aggressive Events. A classic example: instead of sending a Command, you send an Event that implies the need for action.

- Instead of:

dishwasher_finished_cleaning(Passive-Aggressive Event) - Better:

CouldYouUnloadTheDishwasher(Command)

In architecture:

- Event:

reservation_confirmed(Fact: it happened. The Payment module decides what to do with it). - Command:

ReserveRoom(room_id, guest_id)(Intention: execute. The Reservation module decides whether to accept or reject it).

Remember the semantics of messages:

- Command: Expresses Intention. It is directed to a specific recipient and can be rejected.

- Event: Expresses a Fact. It is broadcast and cannot be rejected (it can only be ignored).

Just do not reduce commands to events.

Reducing exposure: internal vs. external events

Your reservation has ten internal states and generates ten granular domain events. Does the Financial Module need to subscribe to them all to know that the reservation is confirmed? Of course not.

Sending all internal domain events to an integration queue is like connecting a public API to private server logs. This leads to tight coupling – any change in the internal process of the module-producer forces the module-consumer to update the subscription logic.

Solution: anti-corruption layer and contexts

Keep two event layers:

- Internal Events (Domain Events): Granular, used inside the Booking Module (e.g. to update the Read Model).

- External Events (Integration Events): Rich, public, issued after key business events. They constitute the module's API.

You can use the Anti-Corruption Layer (ACL) pattern, which subscribes to internal events, enriches them with context (e.g. price, room type, which are not present in the original event) and publishes them externally as rich, integration events. This means that Finance only subscribes to the ReservationConfirmed event, which contains all the necessary data, without having to worry about the internal workings of the Reservation module.

Don't tech-round the issue

Event-driven architecture is about logical composition and organisation (Conway's Law), not tools. Before writing the first line of code and implementing Kafka, make sure that:

- You have understood the business: what is a fact and what is a state? (What/Why)

- You have defined the contexts: How do your teams and modules communicate with each other (Context Maps)? (How)

- Semantics: Do you need a command or an event? (How)

- You have chosen the tools: decide now whether you will use Kafka or something else. (What)

Don't get caught in a trap.

- Understanding the business: What is a fact and what is a state? (What/Why)

- Define contexts: How your teams and modules communicate with each other? (Context Maps? How?)

- Semantics: Do you need a command or an event? (How?)

- You have chosen the tools: decide now whether you will use Kafka or something else. (What?)

Don't fall into the trap of creating a distributed monolith. Don't "Kafka-round" the problem.

Happy modelling!